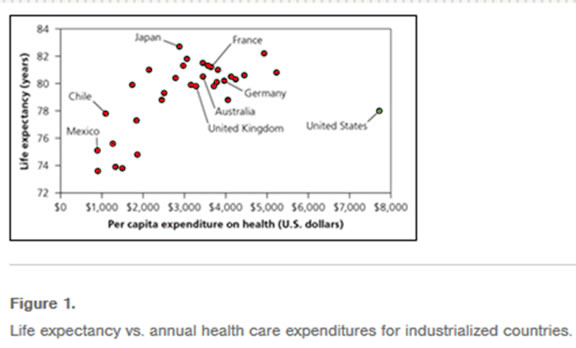

Driving forces for change in the U.S. health care system include the continually rising cost of individual health insurance and the proportion of the gross national product (GNP) used to provide what is loosely called "health care”. Just over 18 percent of the GNP was spent on medical care in 2015. Most of the money is spent on diagnosis and treatment of disease by specialists (medical care), less than 2 percent is spent on health care (promotion or protection of health). An article in Health Affairs, Mar 2006, projects that by 2015 the “Health” spending by the US will be 20% of the GDP! (We are about 18% at the beginning of 2015.) A 2008 study by the G20 countries shows that the US spends twice as much as any of the other developed countries to achieve a lower level of health outcomes. See this recent graphic from the European Community

The issue of the cost of healthcare United States has become even more important since the passage of the "Affordable Care Act" in 2010.

When comparing health status in the United States with other industrialized countries by most measurements of morbidity and mortality, the United States fares poorly. The most recent analysis (2000) by the WHO places Japan as first, with the best health system, and the US as 37Th (see page 13, last column)! Yet the U.S. spends 50 - 100% more of its gross national product on medical care than most of the other industrialized nations. Changing patterns of disease and aging of the population contribute most to the increased costs of health care. A more recent study by the European Union emphasizes this. The January 2013 publication from the IOM “US Health in International Perspective: Shorter Lives Poorer Health” continues the information about the poor outcome of the US health system despite its numerous bright spots

Changes in disease patterns.

Over the years since World War II, morbidity and mortality rates have improved dramatically in the U.S. as has longevity. The major causes of childhood illness at the close of the Second World War were infections. Adults died of tuberculosis, pneumonia, diabetes, heart disease, and cancer. Deaths from infectious diseases in children are rare today, thanks to vaccines and antibiotics. The leading cause of death among children today is violence, with automobile accidents the common cause in young children but homicide and suicide the common causes in teenagers. Among adults, deaths from tuberculosis are rare. The Tuberculosis sanatoria have been shut down and even brief hospitalization is rare, except among ghetto residents.

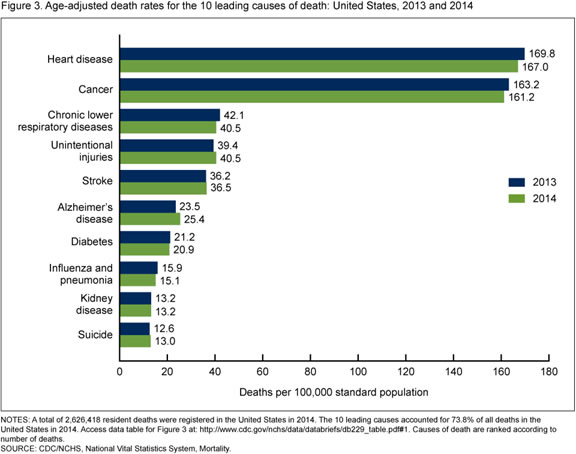

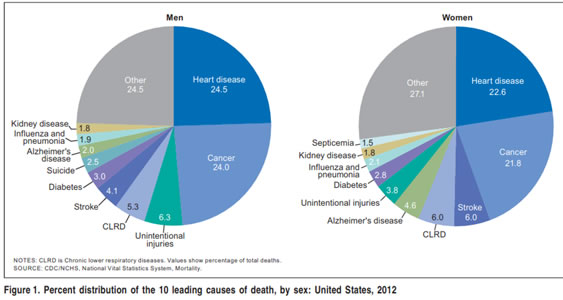

Source NCHS Mortality Data

Looking at death data from 2014 we find that pneumonia, which used to be called the "old person's friend” has become rare, now ranking 15th, and is usually associated with influenza which is further reduced through use of vaccines against influenza and pneumonia. Death from stroke has declined as much as 60% in the U.S. in the last 30 years, while deaths from coronary heart disease, although still common, have declined at least 35%. Among adults less than 55 years of age the main cause of death, as for children, is violence including automobile accidents. For people over 55 the major causes of death are coronary heart disease, cancer, strokes, and diabetes while morbidity from mental diseases such as Alzheimer's disease increases. Further, with delay of death many of the over-60 population are now beset with chronic preventable diseases resulting from unhealthy behaviors such as alcohol use, lack of exercise, weight gain, and lack of sleep and poor diet which is inflating the cost of medical care with a particular emphasis on Medicare. Except for influenza we really see epidemics of infectious diseases in the United States we do have a current epidemic of non-communicable disease [chronic diseases]

The decrease in deaths from infectious and cardiovascular disease has changed the patterns of morbidity, disability, and death requiring a new spectrum of health services with new (or newly defined) and emerging diseases contribute to the problem. Lyme disease, erlichiosis, Hanta Virus, and Legionnaire's diseases have been identified and treatment is available. Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS), caused by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV-I) has been the greatest challenge. Even for this disease new pharmacological interventions are delaying the onset of the disease process, after infection, just as INH prophylaxis brought TB to a relative standstill. We have an epidemic of drug abuse and addiction. Despite the difficulty in finding effective treatment and rehabilitation programs for addictions the average length of life is greater, so that more people are living long enough to become disabled and need long-term care. Advanced technology allows more people to survive, but often with poor quality of life. The high cost of new technology is changing the medical care equation of who needs care for what, at what cost. Despite claims to the contrary, medical care is and always has been rationed. In the U.S. rationing has been by use of financial and sometimes geographic barriers to obtaining care.

Medical indigency

.

Forty to forty two million U.S. citizens (depending whose data one uses have no medical insurance prior to the passage of the ACA in 2010. In 2015 this has been reduced to just over 30 million. They are not covered by their employers, by personal insurance, by Medicaid or Medicare, or by state or city indigent care plans. Of the uninsured, 40% are working poor who have a part or full time jobs, usually in small businesses that cannot afford to pay insurance for the employees and continue to operate at a profit. Changes in the minimum wage have never improved access to health care. A low wage earner will not take a 50-cent an hour increase and use it to buy health insurance. The following data from the US Census Bureau’s shows the current state on health insurance coverage.

Highlights: 2009

- The percentage of people without health insurance in 2009 was not statistically different from 2007 at 15.4 percent. The number of uninsured increased to 46.3 million in 2009, from 45.7 million in 2007.

- The number of people with health insurance increased to 255.1 million in 2009 -- up from 253.4 million in 2007. The number of people covered by private health insurance decreased to 201.0 million in 2009 -- down from 202.0 million in 2007. The number of people covered by government health insurance increased to 87.4 million -- up from 83.0 million in 2007.

- The percentage of people covered by private health insurance was 66.7 percent in 2009 -- down from 67.5 percent in 2007. The percentage of people covered by employment-based health insurance decreased to 58.5 percent in 2009, from 59.3 percent in 2007. The number of people covered by employment-based health insurance decreased to 176.3 million in 2009, from 177.4 million in 2007.

- The percentage of people covered by government health insurance programs increased to 29.0 percent in 2009, from 27.8 percent in 2007. The percentage and the number of people covered by Medicaid increased to 14.1 percent and 42.6 million in 2009, from 13.2 percent and 39.6 million in 2007. The percentage and number of people covered by Medicare increased to 14.3 percent and 43.0 million in 2009, from 13.8 percent and 41.4 million in 2007.

- In 2009, the percentage and number of children under 18 without health insurance were 9.9 percent and 7.3 million, lower than they were in 2007 at 11.0 percent and 8.1 million. The uninsured rate and the number of uninsured for children are the lowest since 1987, the first year that comparable health insurance data were collected. Although the uninsured rate for children in poverty decreased to 15.7 percent in 2009, from 17.6 percent in 2007, children in poverty were more likely to be uninsured than all children.

- The uninsured rate and number of uninsured for non-Hispanic Whites increased in 2009 to 10.8 percent and 21.3 million, from 10.4 percent and 20.5 million in 2007. The uninsured rate and number of uninsured for Blacks in 2009 were not statistically different from 2007, at 19.1 percent and 7.3 million.

- The percentage of uninsured Hispanics decreased to 30.7 percent in 2009, from 32.1 percent in 2007. The number of uninsured Hispanics was not statistically different in 2009, at 14.6 million.

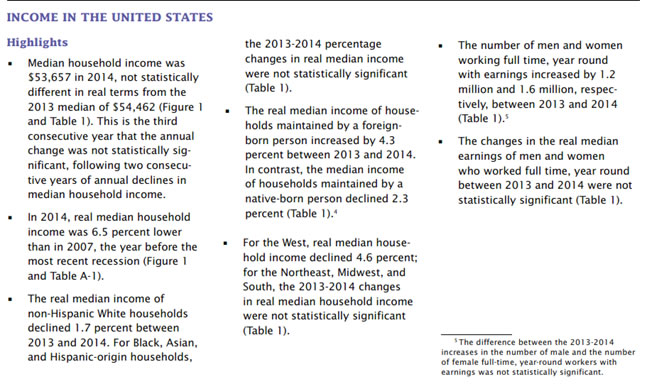

2014 US Income highlights are shown below and useful comparison of development over the previous five years.

Extended data from the U.S. Census bureau can be found at the Census Bureau Website

Medicaid, thought by many people to provide insurance coverage for the poor only covers the poorest people who are either pregnant or recently pregnant women or their minor children. Or those eligible for Supplemental Security Income (SSI) for the aged, Aid to the Blind (AB) and Aid for the permanently and Totally Disabled (APTD). Thus, a single, non-pregnant, poor woman or man cannot obtain health care under any of these programs. In states with ADC rather than AFDC, a married couple with children cannot obtain assistance, although a single mother can. Unfortunately, when the federal government planned health and medical services, few private practice physicians will ask you ed to take part. Public health physicians and local health departments have become the providers of last resort, accepting the responsibility to make up for failures in development of the health care system with limited resources. We can hope this will change once all the challenges to

Affordable Care Act have been met and Congress can clarify the core issues.

Additional up-to-date data and the benefits of the affordable care act can be seen on this website is from the Kaiser family foundation on the uninsured.

Medicaid and the poor.

Medicaid, intended to provide health care to the poor, has been a success for the elderly poor and for children under 18 years of age. For poor people between 18 and 64 eligibility is limited to pregnant women. As a health director in Portsmouth, Virginia in the late 1960s, I analyzed illegitimate births (as a surrogate for children born to broken families) and found that in the ten years before Medicaid became available illegitimacy was never above 13% of births. Within eighteen months of the enactment of Medicaid, illegitimacy had risen to 30% and it has not dropped below that level (in Portsmouth.) but is now starting to respond to intensive national, state and local interventions. Medicaid, intended to help the poor, has instead helped prevent the start of nuclear families, the base of a civil population. Had careful planning gone into the development of Medicaid, this should not have occurred. One of the issues with our political system is the sudden 'all or none' development of programs with little testing before initiation. To some extent the testing is now being performed by national private philanthropic organizations such as the Robert Wood Johnson, Kellogg, Kaiser, and Gates Foundations and the Commonwealth Fund among others, (see their web sites for further data.)

Medicaid eligibility has expanded to include medically indigent women and children under eighteen with income below180% of the federal poverty level, in addition to the other four groups eligible for Medicaid: the permanently and totally disabled (APTD), the blind (AB), those receiving federal supplementary security income (SSI.) The Medicaid program is run by the states, which decide the financial eligibility level for participants for the four categorical programs, those mandated to receive Medicaid, and those eligible for expanded programs developed as federal options for states. In most states Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) income levels are so low (for families with incomes less than 20% of the federal poverty level in Alabama) that few people become eligible for Medicaid. This program has had little impact on the vast majority of the uninsured, except pregnant women, infants and children; or paupers by virtue of being in a nursing home. For several years Congress enacted a series of amendments each allowing, but not requiring, states to increase the percentage of the federal poverty level below which pregnant women and children might be enrolled in the Medicaid program. By 1989 this optional level had risen to 180 % of the federal poverty level. In 1990 Congress mandated coverage of pregnant women and children up to six years of age living in households where income was up to 133% of the federal poverty level. In 1998 the Congress enacted a “Children's’ Health Insurance Program” (SCHIP) allowing states to enroll children in families whose income was up to 200 percent of the federal poverty level into a comprehensive medical and health care program. This program has been enacted in Virginia but far fewer families than expected are enrolling their children into the program. States buy into the Medicare program by using Medicaid funds to pay the premiums for poor elderly recipients. Most of the elderly in nursing homes are poor, either when they enter or within 6 months of entering, or as the result of families divesting themselves of all property and resources to their children, so they can apply to Medicaid as now indigent.

As already indicated, Medicaid, as opposed to Medicare, is a state program for which the federal government matches the state contributions based on a state's ability to tax its citizens. For Virginia the match is 50 state dollars to 50 federal dollars. Other states may match as little as 18 state dollars to 82 federal (E.G. Mississippi). Finding money for the Medicaid match is made more difficult by requirements for the buy-in for the elderly, which adds considerably to the state cost for the Medicaid program. When the program started, more than forty years ago, the proportion of the program used to cover nursing home care for the elderly was less than 10% of the Medicaid budget. Now the proportion of the Medicaid budget used for nursing home care is over 30% in Virginia and rising each year. The Medicaid program pays more than 80 percent of the cost of caring for patients occupying more than 26,000 nursing home beds in Virginia. The Medicaid budget has become the most expensive program among other major state programs such as road building, and education, with an increase greater than any program other than the highway program. It is this increasing cost of the Medicaid budget that has prompted legislators across the U.S. to look for alternate methods to provide financial access to health care, also because the increases in the Medicaid program have helped so few of the uninsured. Currently in Virginia the government and the legislature at a stalemate and the legislature is refusing to raise Medicaid budget despite potential funding from the federal government for the near future.

Other federal mandates and state budgets.

This federal mandate to provide medical services for certain indigent persons is one of many that states are required to carry out. Other mandates, for example, require public buildings to be tested for asbestos and to ensure its removal, if friable. Still others include removal of lead, excess fluoride and other chemicals from public water systems, while others require rebuilding of public sewage systems in many older cities. In Virginia alone, the cost to ensure that drinking water, sewage systems, and solid waste disposal meet federal standards will cost at least $8 billion. All these federal mandates make it difficult for states to find the money needed to implement public health programs to provide medical care for all the indigent, let alone just those eligible for Medicaid assistance.

States attempts to pay for indigent care.

Studies by various state legislatures that have identified the value of providing medical care to the indigent, have given rise to several plans to assure affordable health care for the under and the uninsured. This change in political behavior at the state and community level has been triggered by hospitals that refuse to take care of indigent persons because the cost is bankrupting them. The hospitals claim they cannot survive since Diagnostic Related Group (DRG) payments have been reduced. Since 1989 eighty-eight rural hospitals closed their doors. Several central city hospitals in New York and St Louis, Missouri closed, putting indigent persons at greater risk of poor health. Medicaid reimbursement for physician's services has been so low that many physicians have refused to enroll as providers, or have stopped taking Medicaid clients. This has been most prevalent among rural family physicians and obstetricians.

Limited access to health care for the indigent.

In many states Medicaid pays only 30-40 cents on the dollar of primary care physician's costs of delivering services. This policy has caused physicians practicing in rural areas, where Medicaid eligible indigent persons may comprise up to thirty percent of their practice, to stop taking additional Medicaid patients. Some physicians have left rural areas because they couldn't make enough money to continue their practices. Physicians just completing medical school choose specialties other than family medicine, general internal medicine, pediatrics, or obstetrics-gynecology - the primary care specialties. Those who do opt for primary care specialty training plan to practice in suburbia. Besides inequitable reimbursement, the cost of malpractice premiums and fear of litigation continues to drive physicians from obstetrics. Because poor women are more likely to have a high risk of bad perinatal outcome doctors fear taking them on as patients. In many rural areas no women are able to find obstetric care without traveling 75 to 100 miles to a tertiary care medical center with an obstetric teaching program. This is an increasing problem for local health departments that rely on local doctors to help deliver care to indigent patients. As a final deterrent to keeping health care providers in rural areas, Medicare has reimbursed rural hospitals less than urban hospitals, even for the same category of care. Because many local health directors didn't join their local and state medical societies, or the staffs of their community hospitals, they have missed an opportunity to provide the leadership needed to combat these problems.

Contributing to the shortage of primary care physicians, and the lack of care for the uninsured, is the increased cost of going to medical school. Scholarships are harder to find, and often small in amount. Many students’ complete medical school and head for a residency with => $200-250,000 debt. These debts require monthly payments of $1000 or more just to cover the interest. When they enter practice many physicians owe more than $300,000. Interest payments raise the ultimate cost much higher. Students learn quickly that selecting a primary care practice in a rural or central city area is not likely to bring a salary of more than $100,000 to $130,000 a year, with long hours and little time off for themselves and their families. A surgical specialty, on the other hand, means a salary of $200,000 or more in the first year of practice.

The incentives to go into primary care practice rather than a more technical specialty are very few. Hopefully, some recommended changes in reimbursement recommended by the ACA will reduce the difference between the primary care and surgical specialties. One of these changes is a plan developed between the American Medical Association and the federal government to change the way physicians are paid for their services. A complex formula has been developed that considers the accumulated knowledge, technical skills, and time needed to care for patients. This could increase the payment to primary care physicians while reducing, but not equalizing the reimbursement given to most surgical specialties. This will give better recognition, for instance, of the time and effort needed to care for a patient with an acute coronary occlusion treated medically, compared to the care needed to remove a gallbladder from a patient not acutely ill. The federal government is also considering changing its payment system for rural and central city hospitals. A part of the core of the Affordable Care Act is promote further development and extension of primary care with an emphasis on formation of medical homes for all enrollees.

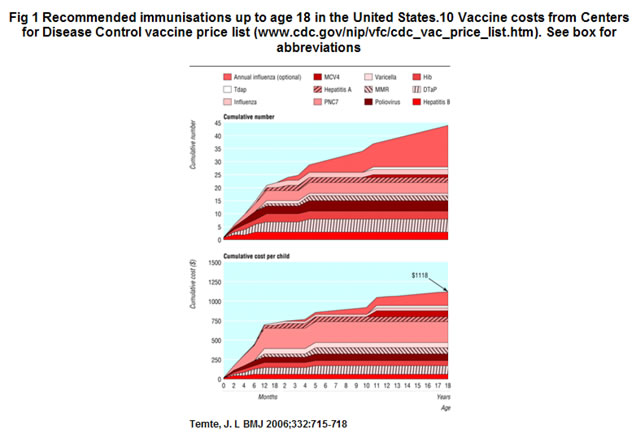

A final example of a problem in obtaining health care is that facing young couples planning to immunize a child. Several years ago, before litigation about the perceived dangers from routine immunizations, a diphtheria-tetanus-whooping cough (DPT) shot cost less than a dollar, now it costs $15 or more. A dose of polio vaccine has risen from a few cents to more than $5.00 while a dose of measles; rubella, and mumps vaccines have each risen from $7.00 to more than $25.00. Thus the cost of four DPT shots, three doses of polio vaccine, a measles, rubella and mumps shot plus immunization against Haemophilus Influenza-B and chickenpox can cost a young couple more than $400. This may be more than they feel they can afford, especially when they hear about so few cases of disease. As new vaccines are developed each year the costs continue to increase, with the recent addition of Hib, Chicken pox, Hepatitis-B, and Hepatitis A immunization costs have risen to $1200 per child which is beyond the means of many young families. However, in many states all the childhood vaccines are provided free of charge to citizens either through local health departments or through grants to primary care physicians.

The graphic below shows in the top graph the cumulative number of cases, and in the bottom graph the total cost by age 18 which in 2006 was approximately $1100 and has climbed since then.

State planning for health care.

Because of the increasing cost to states to care for the un- and under-insured, the loss of rural and central city primary care physicians, and the problems of elderly persons, pregnant women and children unable to obtain basic health care many states are suddenly learning that health care is as important as new roads, schools, and sewers. The increasing cost of providing the local share of Medicaid dollars in addition to other federal mandates has woken up state legislatures. The issues, coming to the surface simultaneously with a need to provide money to care for people with AIDs has sensitized elected officials in cities, counties, and state legislatures. States are finding that their failure to continue to fund health planning, when the federal government ceased supporting it, has left many of them with few options to deal with the health care crisis. Few have any health policy planning mechanism. Now, legislatures are asking consultants, who may know little about state needs but a lot about federal policy, for help. Since local health departments have become providers of last resort to many poor and rural inhabitants they must become planners for health care besides public health services. Though many state and local health departments do an excellent job of long range planning for public health services, few have developed plans to provide medical care, where the crises exist now. In Richmond, as an example of one city, over the last ten years a group has developed to form a Richmond Healthcare Safety Net Consortium.

Public health departments have staff trained to make epidemiologic surveys. Such surveys can be used to plan medical care services for a community. Instead of collecting data on infectious disease they can collect data about hospital discharge diagnoses, home visits by number and reason, and ambulatory care services provided in emergency rooms and doctor's offices. Such data can be used to plan access to primary care early rather than using hospital and high technology care after people become acutely or chronically sick. Reports published by the federal government and in medical journals provide guidance for effective screening services. Medicaid and Medicare data can be used to estimate comprehensive costs of medical care while health department data provides a guide to the cost of preventive services.

States such as Hawaii and Massachusetts and Oregon have started programs to care for all their uninsured citizens. Other states such as Washington and Ohio are planning implementation of services. Yet other states, such as Connecticut and Virginia are planning options to cover the uninsured and entice health care providers to areas lacking primary care physicians.

Massachusetts put a plan into action in 2006 to ensure that access to health services would be available to all its residents. California and Oregon are also developing similar plans. The Massachusetts plan has run into major problems as the costs have escalates past its estimations and many covered individuals have no access to promised care because of the shortage of primary care practitioners,

Local health planning.

Despite the new Affordable Care Act passed by Congress in 2010, there remains an emphasis on containing rising health care costs while the federal government seems unable to put more net resources into health care because the increased population it plans to admit to care will further deplete resources. Local governments still have opportunities to help their states develop plans to assure health services for all citizens. Although the states are the only entities, other than the federal government, with the legal and financial ability to care for all their citizens, local health departments can help their communities to organize physicians, hospitals, and nursing homes to deliver care.

The local health departments may have to change their missions. If the state is to provide an insurance mechanism to pay for medical care the local health department may change its role to coordinating delivery of services, rather than running clinics. It may supplement the care provided by physicians with educational programs for patients to show them how to use medical services efficiently and effectively. Local departments may act as catalysts to sustain rural hospitals on their last legs by obtaining grants from the state government to use excess capacity for primary care programs or services for the aged. The health department can become a primary and preventive care manager for the community.

State Health Commissioners should delegate planning and assurance for community health services to local health department directors who should take a leadership role in this arena, whether or not it is assigned to them. The second decade of the twenty first century continues to be a challenge as reimbursement systems, resources, and the organization of health care are changing dramatically.

The Affordable Care Act.

In 2010 the federal government passed a new law intended to cover 95 % plus of the American population. This act which is controversial, parts have been referred and adjudicated by the Supreme Court, has almost 2000 pages which are so detailed that the tens of thousands of pages of rules (currently more than 90,000) that will inevitably be passed by the Department of Health and Human Services are likely to make it difficult to manage. One can only hope that before the national debt gets even worse that steps will be taken to straighten out this well-intentioned but poorly legislated act. As we move into 2016 there are signs that the concern about the unbalanced federal budget may finally move Congress to focus on primary care and prevention as the base for individual care. But don’t hold your breath!

Systems

Although we talk about health systems in the United States is important to realize that no such organization really exists, in fact what we have is a multiplicity of health systems from federal groups such as the Armed Forces and the Veterans Administration to large organizational groups such as Kaiser family foundation and the Geissinger clinics and professional organizations of physicians nurses, pharmacists and various kinds of therapists, none of which are integrating one with the other and none of which have formal links. This complicated system can be seen in this graphic..

Recommended Reading:

- Fallon LF Jr and Zgodzinski EJ Pubic Health Management 2006. Chapter 34 Access to services.

- Shi & Singh; Essentials of the U.S. Health Care System. 7th Ed. Jones & Bartlett 2007

- Nicola Lurie: Health Disparities – Less Talk, More Action. NEJM 353:7 727-729, Aug 2005

- Fein R: Medical Care, Medical Costs. Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1986

- Guide to Clinical Preventive Services 3rd edition, Report of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. International Medical Publishing Inc., 2005

- Web sites

Kaiser Family Foundation

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation

Gates Foundation

Commonwealth Fund

King’s Fund