2016

Chapter 11

Marketing the Health Department - Overview

> A mix of federal, state, and local monies provide funds for local public health departments. The federal funds, mostly, filter through state health department block grants from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) or the Health Resources and Services Agency (HRSA). A few departments get federal money from special grants advertised in the federal register. Others receive money from grantors such as The Robert Wood Johnson or Kellogg Foundations, of the Commonwealth Fund. Additional money comes from local government for programs such as animal control, or housing inspections. A final source of funds is revenue. The revenue may be payment for approval of permits for septic tanks and restaurant inspections, or may be reimbursements from Medicaid (including the State Children's Health Insurance Program) for clinical services.

Few states are able to provide additional funding for new health services, let alone medical care, due to the increasing cost of the state's share for the Medicaid program, which increases as the population ages, as more people need nursing home care, and as additional vaccines are developed. Primary care services are disappearing in rural and central city communities in many states, although some, like Virginia, are developing innovative linkages and incentives to promote such services, as discussed in a different essay in this lecture series (See VHCF). Local government agencies such as health departments increasingly have to fend for themselves as states pass medical service responsibilities off to HMOs. Local health departments are in competition with every other local government agency for the scarce resources available from most city and county governments (mainly money). Just as health care, roads and education continue to be the major funding problems for state governments, the cost of upgrading water and sewer systems, and providing the local share for education and drug abuse control is bankrupting localities.

Public health departments prevent disease by ensuring clean water, a healthy environment, by immunizations and through targeted clinical services yet get less than two dollars of each hundred dollars spent for health and medical care, from all sources. The visibility of high technology heath care for heart and liver transplants and care of persons with AIDS has diverted money and interest from traditional programs such as family planning, maternity care and immunizations.

Concern for the lack of visibility for public health programs was demons

rated in the 1989 study by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) of the National Academy of Sciences and published as "The Future of Public Health". It stated that public health is in disarray, lacking leadership and commitment at the national and state levels. It was somewhat kinder talking about local health departments, but not much. The main theme of the IOM study was that health departments did not get a fair share of national and state resources because they had become invisible. Health departments had not competed for resources strongly enough and had failed to sell the often dramatic results of the activities they carried out. Failure of the federal, state and local governments to pay much attention to the 1989 study led to an updated study in 2003, also by the Institute of Medicine - The Future of Public Health in the 21st Century. This study, along with funds from terrorism preparedness programs have started a move to better management and attention to community health services.

Many effective public health functions such as permitting installation of home sewage and water systems, inspection of restaurants to prevent the spread of hepatitis-A and other enteric diseases, provision of immunizations to prevent common childhood diseases, education for family planning and provision of maternal and child health services are provided without fanfare. They are seen as routine and public health activities. Staffs have carried them out for many decades and assume everyone else automatically sees their benefits. The public however, hears about old people, who cannot afford nursing homes, or people who cannot afford heart and liver transplants, or people who cannot afford acute medical care. They hear about the rapidly rising costs of medical care, but not about money saved because children were not dying from measles, or people are no longer affected by many outbreaks of enteric diseases (Although recent food borne infections are starting to bring this awareness back). The community hears about the high costs of infant care in neonatal units and looking after "crack" babies, but never about the resources saved because parents given prenatal care do not end up with children in neonatal intensive care units.

Further detracting from visibility of health departments has been the move of state governors to form environmental departments. This was done in response to concern about cancers, said to be caused by damage to the environment from wastes discharged into rivers from factories, or into landfills later used as home sites. For many years health departments had been responsible to ensure that people were safe from toxic substances in the air, soil and water, but now these services have been moved to specialized agencies with high visibility, usually managed by lawyers or engineers untrained in toxicology or cellular damage, but who understood how to manage the media to show how well the governors were responding to public concern, something the health departments had not done. Despite paucity of evidence that any damage occurred to people much publicity followed incidents such as disposal of wastes by the Hooker Chemical Company at Love Canal in New York, or washing of Kepone wastes into the James River in Virginia, or DDT into the Tennessee River in Triani, Alabama.

The IOM studies on the future of public health identified a major task for public health departments; to come together and explain clear goals and objectives to improve the public's health. The IOM recommended that health departments, at all levels of government, develop goals to improve health by the year 2000. Like most goals for health care, this was not reached or even approached. The base for public health plans at federal and state levels has been the series of Healthy People plans. Very few of the objectives for the 27 focus areas have been met which gives politicians the message that public health cannot perform its tasks. The latest plan (Healthy People 2020) contains no references to toxic wastes in its goals or objectives.

The Health Department's Role.

Local health directors must take part in goal setting. Virginia, California and Texas are examples where state and local health departments joined to develop long range plans, first to reach the mid-1990s and mid 2010’s and now to look ahead to the year 2020. The plans developed over the last 30 years with a series of iterations:

These objectives initially focused on disease prevention, health promotion, and health protection with five objectives in each area. These fifteen areas were expanded to 21 major goals with over 250 objectives with the HP 2000 program and to 28 Major Goals with hundreds of objectives in the HP 2010 publication. Besides these national goals and objectives local health directors in many states, acted on, currently are focused on corrections from the 2005 midcourse review. Finally the HP 2020 provides a more coordinated but very extensive set of objectives and priorities which are very useful nationally but needs modification at the state and local levels. The IOM recommends assuring financial and physical access to primary care services, a major component of which is prevention of disease. The large number of Topics and objectives in the HP 2020 program tends to detract from a focused approach to goal/objective achievement at the local level go to sleep go to sleep.

Many local health departments have selected specific health objectives to which they can target their marketing objectives. These marketing objectives should be internal and external. The internal objectives relate to selling the department's staff, and sister agencies, on mutually defined objectives and helping define work plans that will change the function of some staff members while making the role of others broader. Evaluation of progress in achieving objectives requires good data.

Despite continued limited resources, health directors may decide to use some of their budget to develop better data systems that will allow changes to be measured when they occur, thus validating their actions. The same data system also may measure the cost and effectiveness of different processes. The data may lead a health director to modify the department's objectives.

For example the department might shift funds to provide additional immunizations that require more staff time, as well as records, equipment and storage. Alternatively, the director may spend less money to purchase vaccines and provide them free to physicians, with the understanding they will not charge for the immunizations, but will provide a list of people immunized. This may be a better use of resources that should be demonstrable by accumulation of specific data such as the immunization level of children entering day care centers.

Similarly, the department may decide to use limited sanitarian capacity to monitor septic tank installations but require homeowners to hire soil scientists and civil engineers to plan, locate, and install the systems. This transfers much of the cost of installation from the health department to homeowners. This reduces spending state taxes in competition with private industry. The dollars freed up can be used for other programs rather than to hire sanitarians. The director may decide to hire fewer physicians and use nurse practitioners in their place. Whichever strategies you use, the whole plan must be sold to the department's staff. Internal salesmanship (gaining the staff's acceptance for new procedures or programs) can be successful by involving the staff that will be affected in the planning so they can help to choose between future alternatives. Integrating staff members into goal setting and problem solving helps them become part of the solution and lead them to recommend role changes without feeling they were forced into the change.

The department also has to sell its goals and objectives externally, to other health providers, health related groups such as cancer and heart associations, civic groups such as leagues of women voters, fraternal orders, civic groups and service clubs such as Rotarians or Lions clubs. These groups often form the health conscience of a community and become strong advocates for the health department. In addition it is necessary involve the people who need specific public health services such as the young, disabled, aged, and minority. Each group wants to know that they are getting some benefits from the department's activities, which are funded from local tax dollars and fees. They can help to sell your programs to the elected officials who also listen to other government agencies and citizen groups with competing needs. In addition to elected officials you must sell the department's programs to the officials appointed by those elected to office, who actually administer the city or county government. A useful ally in selling your programs to elected officials is a local board of health composed of members appointed by the local officials. Members of a board provide instant credibility with the elected officials who recommended them for the board. Finally you need assistance from the television, radio and newspapers.

Selling the Department to the Media.

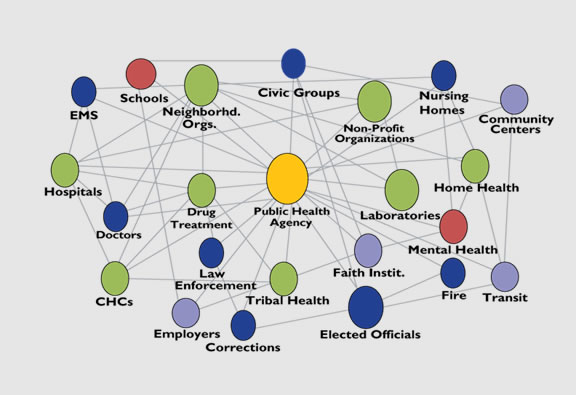

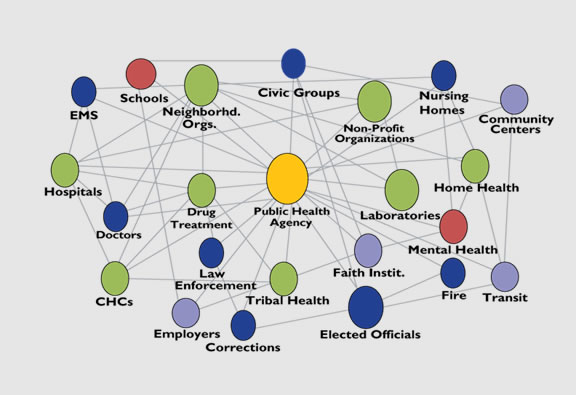

Besides making department staff part of the community support system, a health director must identify the media personalities who can help publicize the department's actions. Find out if any of the local reporters have science backgrounds. See who covers city hall. Check what and how well they write. Work with staff members to plan timely periodic releases about the department's activities (one of our local reporters completed the MPH program at VCU). Many opportunities arise for local health department staff to appear on talk shows with TV and radio personalities. Such opportunities occur when there is a local outbreak of measles or hepatitis, or when national media carry special reports on the ill effects of smoking, or report deaths from exposure to toxic products, report on radon in homes, pesticides in milk or the value of special diets. Each report provides an opportunity for an alert health department staff to appear as expert consultants, discuss potential local exposures and how to avoid them. Have material ready for local science reporters. Identify and coach staff members who enjoy going on TV or before a live microphone. Each appearance is an opportunity to sell the department. When there is concern about the environment, make sure the department's environmental programs are shown to be effective. When stories appear in the media about potential health problems find a way to give them a local slant. Don't hesitate to agree or disagree with activist groups when you are sure of the scientific basis for your comments. Many of these groups are well meaning but often work from feelings rather than facts. Environmental stories about leaky storage tanks, ozone layers, EDB, PCB, DDT, etc., all deserve your attention. Make sufficient contacts, using all appropriate staff members, so the department can provide rapid news releases and comments on national and state stories from a local viewpoint. Many public gatherings such as city councils or boards of supervisors, garden clubs, community health days, and fund drives of health related agencies such as diabetes and arthritis associations provide opportunities to improve the department's credibility. Make sure the staff receives as much public credit as possible for day-to-day efforts. When discussing how to use media to focus on public health systems is important to consider all the members of the system as shown in the graphics below:

Selling to Health Care Professionals.

Besides working with the media and public groups, don't forget other health care organizations such as the medical and dental societies. You can market the health department after assessing disability and death in the community by sensitizing physicians to the role lifestyle plays in causing disability and death. Encourage them to report the use of tobacco, alcohol and other drugs, as well as obesity, on death certificates. Provide physicians, nurses, dentists and pharmacists with maps showing locations of deaths by place of residence and cause of death. The maps, prepared with data from your vital statistics programs, as described in previous lectures, can show that diseases linked to lifestyle occur in all socioeconomic areas of the community.

Maps can be good marketing tools to use with both the public and health professionals. The distribution of STDs by age, economic level, education, and residence, when reported often enough, makes the point that cure is not as satisfactory as prevention when dealing with common diseases. Maps showing the incidence and prevalence of chronic diseases such as coronary disease, diabetes, cirrhosis of the liver and lung cancer can be used to encourage all physicians to question their patients about their lifestyle. When appropriate, physicians can refer their patients to community programs, which assist in changing adverse lifestyles. The maps can be used to support the department's educational efforts to change habits such as smoking, drinking and overeating by focusing efforts in those geographic areas containing most people dying from diseases caused by adverse lifestyle. Maps are also good visual aids to use while speaking on a television show or providing a story to the newspapers.

Public Education for a Specific Problem.

Health education should be targeted to prevent infectious and chronic diseases. This is an opportunity to show the community the knowledge and skills present among the department's staff. The staff can present programs on control of infections such as measles, syphilis, tuberculosis, and hepatitis-A and B, and AIDS to hospital staffs, dental societies, and PTAs. These groups have special interests in health. Healthcare workers are concerned about becoming infected by their patients. Many communities worry about hepatitis-A, shigella, and salmonella but think they are caught only in restaurants. Educational programs should describe the potential reservoirs for fecal-associated diseases. They should be given to day care centers, restaurants, and nursing homes. The most important message should be the need for hand washing as the first line of defense against transmitting infectious diseases.

Because many infections occur sporadically in the community, people are only kept alert about the likelihood of being exposed if they receive regular reminders either by direct mail, from school nurses, their doctors or by messages from the health department in newspapers or on radio and television. Toward the end of the school year and a month before school starts, put out information about the need for immunization before admission to school. In the early fall, talk about influenza and pneumonia. In the winter start alerting the public about visits to the countryside in spring and summer that can expose people to ticks, fleas, mites and flying insects that can cause Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, endemic typhus, Chagas disease, Lyme disease and plague. When summer is approaching, place stories in the various media about vacation- associated diseases such as "traveler’s trots" and mosquito borne diseases like malaria, dengue, and yellow fever. Remind vacationers about the potential for getting Hepatitis-A when traveling abroad. These and many other infections make excellent stories when released with pamphlets and carefully targeted to different times of the year and through different media.

Providing a Balance.

Information provided to the media should not be concerned only with public health services. Discuss topics that, while health related, may not be directly targeted at health department services. Provide a balance between programs, which inform the public about the department's services that promote health by education as well as providing general health information. For example, discussion of control of childhood infections usually supports a specific goal of the health department. Discussion of the effects of eating too much fat, or putting fiber in the diet focuses on maintaining general health. Discussion about international travel requirements for specific vaccines is useful to all travelers. With the increased cost of health services in mind provide regular releases about these costs, the type of insurance needed, how to shop for health services, and when to obtain a second opinion. Planning these releases with the medical and scientific community, local hospital(s) and nursing home(s) builds cooperation and trust between the department and important community healthcare organizations.

Selling Other Community Agencies.

Besides working with your peers in the health care field, co-operate with other agencies such as social services and mental health to exchange data about mutual clients, to reduce paper work and plan care for patients jointly. Take opportunities to support and help other departments such as police and fire departments by teaching CPR courses and ways to prevent infections when caring for injured people. The goodwill that develops is another important marketing tool. If you have problems with an agency, discuss it with the agency head privately but be supportive in public. The friends you make should be friends you keep. Develop ties to the lung, heart, diabetes and arthritis associations. Try to serve on boards of the United Way and health organizations such as the cancer or heart associations.

Targeting Elected Officials.

Officials elected to state and local offices provide most of the money for public health programs. These officials must see the department as an active progressive agency, out front protecting the health of citizens from real, not imagined causes of disability and death. Tell them what barriers stand in the department's way of serving their constituents, and how they can help the department. Be ready to write talks for them. Provide them with data when they go to the state capital. Let them know how their support of state agencies results in additional help for their voters. Help them understand the difference between incidence and prevalence. Let them know how educational programs can minimize problems such as AIDs, alcoholism, lung cancer, suicides, and homicides. Elected officials can be of immense help, when properly nurtured. For example, changes in state law allowing passage of local ordinances to control housing standards, can help their electorate and cost little money or effort.

Taking the Media with You.

Whether briefing reporters, elected officials, or people at large, only hold back information if the listener or reader may be misled because not enough facts are available, because a criminal sanction such as quarantine is contemplated, or because you need to give others affected by your actions information directly, rather than through the media. When dealing with sensitive topics it is important that the department does not look as though it is hiding, or lying about, facts. The health director must be in control of health-related information. Try to give clear, simple explanations to the media. Whenever possible, provide visual aids to help explain scientific issues. When managing an outbreak of hepatitis-A for instance, I once took some television and newspaper reporters and photographers on a ride around the community, including our clinics. I wanted to show them all the discarded disposable diapers. The diapers outside our clinics were often fresh and full of feces. A few shots of these on TV and in the newspapers, with more graphic descriptions on the radio, plus visits to the school superintendents and principals, and nursing visits to day care centers, reduced the number of improperly disposed diapers. Still, although I wanted to improve hand-washing, I never could get grocery stores to put notices on the racks where they kept the diapers, or on their grocery bags to describe the danger of improper use and disposal of diapers!

In conclusion, a clear short- and long-range public health information and education plan, including costs and program alternatives, is needed to market your product: health promotion and prevention. The plan should include routine periodic messages to alert the media about potential incidents, such as increased rates of STDS, food-borne outbreaks of hepatitis, unchanged infant death rates, low weight births and developmental disabilities. Take advantage of newly breaking health promotion stories so that local media can offer a local view of state and national news. Identify, in advance, staff who can respond to specific news items. Keep the department's image in front of the public. Always have printed and visual information ready to distribute that will illustrate issues such as prenatal care and family planning as they affect developmentally disabled and retarded children. Make similar preparations for stories about STDs, immunization, environmental assessment, stroke, lung cancer, diabetes, heart disease.

Finally, an untapped source for many health departments is the Internet. Many local governments provide a web page for their health department which lays out the available programs but does little to connect health and medical providers together, or emphasis the value of case management, or more importantly prevention of chronic diseases. Rather than requiring citizens to search the web, local health departments should work with other health and medical providers to set up community health 'Portals’ which link citizens to all the various categorical support groups, that link citizens to health promotion programs, and educate people about the role of public health other than the provision of categorical clinics for the indigent.

Recommended Reading:

1) Fallon FJ Jr & Zgodzinski EJ, Public Health Management: 3rd Edition; Chapters 19 & 20. Marketing Public Health. 2013