2017

Chapter 2

ORGANIZATION AND ADMINISTRATION

The effectiveness and efficiency of any health department depends on the type and number of programs, staff size, and the department's relationship with any other parts of the organization. Administration of the department requires both careful analysis of physical and human resources and a proper meld of individual skills and management techniques to carry out its mission. This is illustrated by comparing a state and local health department (see Figs. 2-1 to 2-5), as in the Virginia Department of Health, which serves as our model. However, the management principles, and the relationships among local and state health officials, are similar elsewhere. All state level agencies in other states will have similar sets of responsibilities to those discussed in this “model” agency.

DEVELOPING ORGANIZATIONAL RELATIONSHIPS

When developing a health department's organizational structure, it is ideal to group similar activities together, such as environmental services, prevention programs, medical care, administration and support, and regulatory programs. It is sound management practice to give supervisors a reasonable span of control. A good rule of thumb is five to seven individuals per supervisor. This link demonstrates the variety of programs found in state health agencies.

THE STATE HEALTH DEPARTMENT

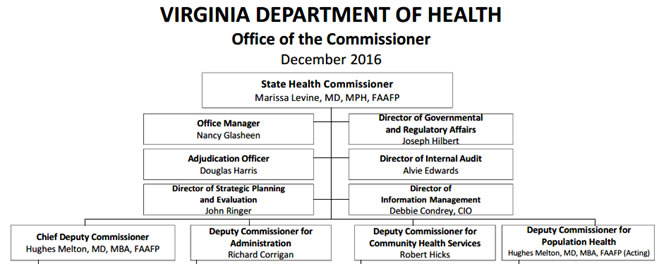

In a state health department, illustrated in Figure 2-1, the Commissioner of Health usually has several senior managers such as Administration, Public Health Practice, Community Services Programs, and Emergency Preparedness. The commissioner will also have a number of advisors in specific areas who are not administrators like the deputies but whose job is to provide expertise in such areas as internal audit, Information Systems, and Regulatory Affairs. This gives the commissioner a span of control of six to eight people. Everyone, other than the commission's advisors, in the organization reports to one of the first line managers Deputies). Such an organizational approach is imperative in any large organization. Although lines of authority from the health director to field staff lead directly from top to bottom, the department's operation is best managed by teams that cut across these lines. While these diagrams for Virginia are typical of many states, the organization may change annually or only a when a new governor takes office.

2.1 - Office of Commissioner Dec 2016

|

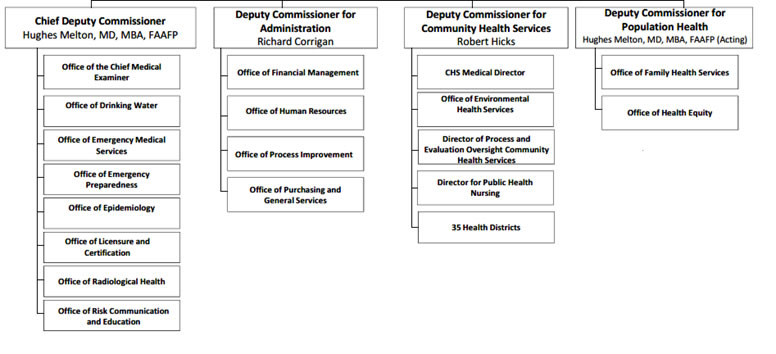

2.2 - Departments/Offices reporting to Commisisoner’s Deputies, Dec 2016

2.3 COMMUNITY HEALTH SERVICES - Health Districts in Virginia

|

|

The line manager for field operations, the Deputy Commissioner for community health services, has a span of control of six staff members and 35 health directors who manage the local health districts (see figure 2.3 above). Each district in Virginia is intended to contain a minimum of 100,000 people. The division of the state's 91 counties and 45 cities are combined into health regions and districts is shown in Figure 2-3. In addition to the district directors, the deputy supervises four technical groups that deliver most of the health department services to the community: the chief nurse who coordinates nursing issues for the deputy commissioner and is responsible for long-range planning and recommendations on nursing needs within the state, the director of environmental health is responsible for home-site sewage systems in a district, as well as food programs and milk standards by supervising environmental specialists, an overall medical director to advise on local health districts, and finally the district administrator responsible for budget and administrative staff. The health districts in Virginia have between 100,000 and 700,000+ residents. The districts may be a single county or a multicounty/city collaborative. Other states often organize local districts differently.

Through these senior staff, the deputy commissioner for community services is responsible for hiring and firing staff, management of the district budgets, and planning for statewide services. This individual coordinates delivery of services by the field staff according to program standards developed by, the deputy commissioner for health care services. This official also develops the technical standards for local district budget preparation and analysis, procurement, and compliance with personnel standards with a third deputy (administrative services.)

Following election of a new Governor and appointment of a new Commissioner, in 2014, the State Health Department was reorganized with the chief deputy for public health becoming responsible for statewide technical personal health services such as family planning, maternal health, infant and well child care, as well as statewide technical problems such as epidemiology and surveillance, toxicology, health education, genetics programs, developmental disability services, and nutrition programs. These services fall into the three major areas of health programs, each of which has its own manager. Further, this group is also responsible for certain statewide standards of environmental health services which include municipal water and sewage systems.

The administrative manager is responsible for the infrastructure services of hiring, equipment purchase, accounting and internal control and information services which over the last few years with federal leadership has developed into a major program linking federal, state and local health agencies together and developing record systems for individuals served in the community health services programs.

Since the World Trade building disaster the office of emergency preparedness reports to a chief Deputy Commissioner has become responsible for all facets of emergency preparedness that have a health impact, whether environmental disasters or disaster such as plane and train wrecks or environmental hazards from hurricanes.

Each manager is responsible for supervision of federal funds, which have different standards of accountability from the state funds with which they have to be matched; therefore, these managers must have fiscal and budgeting skills. Program managers are also responsible for developing statewide performance standards that local directors can use to evaluate and modify services.

TEAM DEVELOPMENT

Many program managers, who deal with technical services, rather than coming face-to-face with the clientele served, make arbitrary decisions that could hamper delivery of health care in the community. To reduce this tendency, it is best to form task forces, or teams, to set standards and performance goals. The teams should consist of technical experts within the central program office, experts from the field and regional office, field staff who deliver the services to clients/patients, and, when appropriate, academic and community representatives.

For example, a team developing standards of performance in perinatal clinics could be made up of staff nurses, nurse midwives, obstetricians, administrators, clerical staff, and directors from local health departments, regional maternal and child health nurses and directors, and prenatal staff including nurse specialists, records administrators, and fiscal managers from the central program staff. It may be necessary to have more than one team for complex programs supported by a coordinating team headed by the appropriate deputy commissioner. It is often useful to have representatives from other agencies. When working with children, one should select representatives from school and mental health systems and advocacy groups. If working in food service, it is best to invite representatives from both the department of agriculture and from the wholesale and retail food service industries. The use of special teams permits a thorough discussion and evaluation of most issues affecting the funding agents, the service providers, and the clients receiving the service. It is also advisable to have public hearings to allow special interest groups to make their points.

All decisions reached by the deputy for health care services should then be brought before the commissioner's staff for discussion to guarantee that all ramifications have been studied and that the impact on the management area of each deputy has been approved.

Additionally, an internal auditor needs to be able to certify to the commissioner that there will be an acceptable audit trail for all expenditures. The deputy for governmental and regulatory affairs must be assured that interests of various legislators (particularly those who wrote enabling or appropriating legislation) have been reviewed before final decisions are made. This deputy is also responsible for chairing a number of advisory boards, which help develop statewide policy and provide advocacy when needed. These include advisory groups on radiation, toxicology, perinatal services, and AIDS.

ADMINISTRATIVE AND REGULATORY SERVICES

The deputy commissioner for administration in the state agency reviewed here has responsibility for fiscal accountability. This deputy is the individual who certifies to the state department of accounts that the fiscal balance is positive and will remain so. (Virginia, like most states, is not permitted to develop deficit budgets.) The deputy for administration has four major program area managers: one for financial services, one for personnel (human resources) services, one for performance and planning services, and one for purchasing and general (housekeeping) services. Special technical staffs with direct access to this deputy include the director of data processing (sometimes called "information services") and a specialist in organizational development. This deputy also has an executive secretary and is responsible for health planning advisory boards. The deputy for administration is a key contact for city and county managers, who usually have similar fiscal and planning backgrounds. Budgeting, fiscal analysis, and planning will be discussed in a separate chapter.

THE MEDICAL EXAMINER

The chief medical examiner is a manager who reports to the state health commissioner in many states. This ensures medical supervision in states where, by law, the commissioner must be a physician and provides resistance against political pressure to make this program a law enforcement activity. The medical examiner is responsible for certifying cause of death under certain circumstances such as homicides, suicides, and accidents, as well as for individuals dying without a medical attendant. The medical examiner often works outside the public health system. In Virginia, the medical examiner has four regional offices that work with community physicians to make the initial determination of cause of death. Only when the cause is not certifiable by the local medical examiner does the chief medical examiner become involved.

THE INTERNAL AUDITOR

In Virginia and many other states, an internal auditor reports directly to agency heads. They certify that programs are run effectively and efficiently, or else make recommendations for improvement. The internal auditor is reviewed by a state auditor, who reports to the governor. There is also an auditor of public accounts, who reviews state agencies for compliance with state and federal law. The department's internal auditor reviews all programs in the department on a (five-year) cycle. Field operations are reviewed mainly for fiscal accountability to ensure that proper expenditures are made, correct control documents are completed, and safeguards against fraud are in place. In the central office, similar fiscal audits are made. The internal auditor is responsible for reviewing the programs funded by the legislature to ensure that department managers spend funds effectively and efficiently. Such audits are based on sample documents from programs and provide senior managers, including the commissioner and the deputy commissioners, with additional checks of program performance.

LEGISLATIVE LIAISON

A legislative liaison, in Virginia the advisor for Governmental affairs in the commissioner’s office advises the commissioner and senior staff about inquiries from any elected official. The liaison also coordinates staff appearances at legislative committee meetings or attends these meetings personally. This individual coordinates agency activities with the legislative staff of the budget, appropriations, and health committees of the legislature. He or she disseminates all rules and regulations adopted under the state's administrative process act. The liaison is a point of contact for members of the state board of health when the commissioner is not available.

THE DIRECTOR'S SECRETARY

An important person in the commissioner's span of control is the executive secretary (office manager), who completes all the commissioner's letters, reviews all mail addressed to the commissioner, checks all documents signed by the commissioner for correct grammar and spelling, ensures proper protocol for forms of address, and keeps the commissioner's schedule of appointments.

STATE COMMISSIONERS AND GOVERNORS

The governor's office in Virginia, rather than having over 100+ large and small agencies report directly, a patent impossibility, has a cabinet with several secretaries. One of these is The Secretary for Health and Human Resources [currently Dr. Bill Hazel], to whom 16 agencies report; Figure 2.4. Several agencies are large, such as health, mental health, social services, medical assistance services (Medicaid), and rehabilitative services. Smaller advocacy agencies, such as rights for the disabled or an office on aging, also report to the secretary. Only those decisions that require the governor's approval go to the governor. This arrangement ensures that agencies with interests in health coordinate their efforts before seeking the governor's attention. In some states, the health commissioner reports directly to the governor, in competition with a myriad of health and non-health agencies.

SPANS OF CONTROL

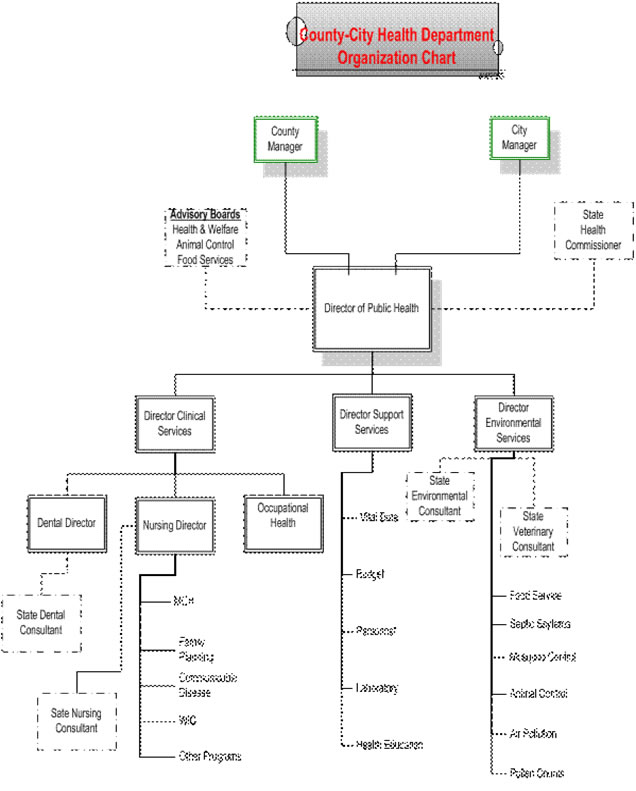

The commissioner's span of control is very similar to that of a local health director as shown in Figure 2-5. The main difference is that there are fewer staff members, and fewer and less complex programs, at the local level (except for the 10 to 12 largest cities in the country e.g. New York, Los Angeles). Organizationally, local health departments have programs and chains of command that are similar to those at the state level. Technical supervision of staff, however, is usually performed by state or regional program directors.

The Governor’s Office

VA state Government web page shows the organization of state government in Virginia, including the judicial and legislative agencies

Figure 2.4

Chain of Command from Governor (Virginia) to State Health Commissioner through Secretary of HHS

A MODEL LOCAL HEALTH DEPARTMENT Fig 2.5

THE FORMAL CHAIN OF COMMUNICATION

Communication between the vertical and horizontal layers of the healthcare hierarchy is very important. All state directives should be channeled through the appropriate commissioner's deputies and through the regional and local health directors who have the fiscal and administrative responsibility for delivering services. Failure to do so often results in confusion at the local level. This confusion may occur because technical staffs don’t know all the budgetary, fiscal, and operational issues that have to be coordinated to develop statewide policy. This does not prevent technical issues not requiring operational or administrative changes from being discussed between peers at different levels of the organization.

The local health department's structure (Fig. 2-5) illustrates the division of responsibility. Managers of some programs, such as health education, may report directly to the local director, rather than through the local department's administrator, although the health educator operates more as a departmental support service to the other functional programs. A local laboratory director is also likely to report directly to the director when seeking technical support and direction. It is in fact a mini version of the State Health Department in Virginia and other states that are similarly organized.

Many local departments have a set of clinical programs, although they may be prevention oriented rather than therapeutic. These include prenatal care, infant and well child care, growth and development programs, immunization, dental care, and infectious and chronic disease surveillance. Larger or more sophisticated departments may also have an occupational health program concerned with local government employees' health while on the job. The director of the occupational health program usually reports directly to the health director. In large cities with indigent populations and in some rural areas as well, the local health department may be directly responsible for primary medical care and school health services. Some local health departments are also responsible for mental health services. Because of changes in federal law, mental health services in most localities are administered outside the public health system, although there is often close coordination at the community level. Many "mental health" services are more like social services; they are aimed at the behavioral function of individuals and families rather than the treatment of disease. Health departments that are responsible for these programs may do well to develop a network of mental health-social support services or provide support to social and family service agencies. The failure to set clear objectives in this field has led to much redundancy and inefficiency.

A very few localities around the country, such as Arlington County in Northern Virginia, have eliminated barriers between human service agencies and meld them tougher into a single human services agency and have a single data system which enhances services to households and reduces paperwork and bureaucracy and ensure that services to a single family ae coordinated . When you are looking at the Arlington web page be sure to click on the Health link.

In addition to clinical services, all health departments have an environmental section. In many local departments, the focus of this section is individual sewage-disposal systems and restaurants. In other departments, the environmental section has an animal control program to prevent injury and disease from animal bites and to deter spread of zoonoses for which pets can become reservoirs, such as salmonella, Lyme disease, typhus, and plague. The environmental section may also have a mosquito-control program to prevent spread of diseases such as malaria, dengue, yellow fever, and encephalitis, particularly in the southern and western United States.

An increasing interest in waste disposal is making the employment of toxicologists, engineers, and chemists more common in larger local as well as state health departments. These professionals help the local departments advise their communities on imminent health hazards to humans from ground, water, and air pollution, as well as toxic spills. Although state agencies usually play a large role in environmental assessment, the increasing complexity of federal programs and lawsuits by environmental activists require localities to have such technical expertise available. This expertise should be given to local health departments, where the combination of environmental specialists and physicians trained in epidemiology is most effective.

NEED VS. DEMAND

As public health becomes more complex, it is important that local administration be both effective and efficient. There are always more health needs in a community than there are resources to deal with them. This is true for single agencies such as health departments, groupings of agencies such as human resource groups, and entire local governments. This unmet demand exerts pressure on clinical and environmental programs. Current concerns about sewage and toxic-waste disposal have made both siting and soil evaluation more complicated. Many local health departments find themselves cutting back on other environmental services, such as food protection (a political decision rather than a health policy one.)

LOCAL SPANS OF CONTROL

It is a director's responsibility to develop goals, objectives, and standards. Setting goals and objectives is discussed in Chapters 3 and 6. Setting standards is essential to good administration and deserves attention here. Among a health department's standards are those that cover staffing patterns. Neither a health director nor a supervisor should have more than seven to eight people reporting directly to that person. Unfortunately, management principles are often taught in a vacuum within government. Elected officials are more likely to approve additional field workers than supervisory staff. It takes as much skill to supervise a nursing aide or a clerk as it does to supervise a nurse, environmentalist, or physician. Supervisors must know the breadth, depth, and frequency of their staff's activities and be conversant with their level of performance. They ensure that knowledge and skills are kept current by repetition, supervision, and education. They also ensure the accuracy and effectiveness of the work done by staff. There is nothing more important to good supervision than periodic review of individual performance.

DUTIES OF SUPERVISORS

One of the most important duties of supervisors is to maintain staff morale, and ensure that staff members are satisfied with their work, and select those who will benefit from additional training and can be expected to rise to management levels. Supervisors need to have enough experience to know that staff members have enough work to keep them busy but not so much that they have to work overtime. Work should be sufficiently complex to challenge each person's performance. The ideal employment pattern is that no job is done by someone trained for a higher level of work. Nurses should not do practical nursing work, practical nurses should not perform clerical work, and clerical staff should not perform housekeeping tasks. Each person, ideally, should have to work at maximum skill levels to perform his or her job effectively.

CARING AND TIME MANAGEMENT

Current federal and state labor laws prohibit unpaid overtime. Few departments can afford to pay overtime. It is no longer acceptable to allow staff to work overtime because there are "people out there who need to be seen!" Many nurses say that they don't mind working additional hours if people need their services. However, they expect to be given advanced merit raises because they work overtime, or because they often work "for free.” Eventually the nurses will become dissatisfied with their work or their supervisor. Then they look for a way to express their dissatisfaction, frequently by asking how they are going to be reimbursed for the extra hours they put in at no pay. This may lead to morale problems. It is the supervisor's job to provide guidance so staff does not work overtime, without compensation, and become burned out.

MERIT SYSTEMS

The goal of a merit system is to assure that all employees are compensated equitably. Most merit systems require the managers to study prevailing pay rates for similar job classifications. Then an appropriate pay scale is developed that will not deter people from seeking work and won't be excessively costly to the taxpayer. Thus, merit system pay scales in government are not as good as in private industry. They usually lag 2 to 3 years behind the private sector. There is no requirement that merit system pay scales be equal to any similar pay scale in the private sector, only that they be competitive. The test of a pay scale's adequacy is the number of available positions in that system compared with the number for similar positions in other government agencies or in private industry. The individual payment steps, pay range, and benefits should be similar. Managers must counteract staff perceptions that government is required to pay at the top rates of competing organizations.

FRINGE BENEFITS AND PAY

It is also important to look at non-monetary compensation such as paid life insurance, retirement policies, health benefits, and vacation days. Staff members usually look only at net pay. They frequently forget that fringe benefits differ among different organizations. One problem with government merit systems is that they pay the average of similar jobs located in different parts of the state. This may benefit employees in depressed areas but hurt those in high-income, low-unemployment areas. Step increases, based on annual evaluations and separate from cost-of-living increases, are also important to prevent excessive vacancy rates and keep staff satisfied with their overall benefits package. Through a combination of longevity pay, increased-skill pay, and bonus pay for above-average performance, some communities and many private firms provide increasing benefits over 20 to 30 years. Many communities and states allow staff members to reach their maximum pay level in 8 to 10 years. This is unfortunate, because it puts civil servants on the shelf after 10 years. There is no incentive to keep working productively, only to work enough to protect one's pension. The way to get around this limitation is to change the pay package every few years and grant pay increases even to those staff members who have been with the organization a long time.

PLANNING STAFF UTILIZATION

In addition to personnel benefits, there are benefits in good supervision, constructive criticism, team building, and opportunities to improve skills and advance in status. These are some of the most important tasks of supervisors. Staff needs to be assigned jobs that allow them to demonstrate their skills that allow them to feel they help both the agency and their clients/patients. They need to know their assignments far enough ahead to plan for them. Assignments should take into account the members of the team who will be away on vacation or training so that clinics or inspection programs will have enough staff to carry out the essential elements of the job. Failure to schedule staff properly reduces supervisory effectiveness. Staff members feel the supervisor doesn't care about either the clients or the staff. In clinical programs, where local physicians and physician extenders often provide part-time service to the department, it is easy for these individuals to lose their interest in the clinic if, having taken time from a busy office practice, they must sit around while clerical chores are performed.

THE ANNUAL EVALUATION

Personnel systems all require annual employee evaluations. Many supervisors look on these annual evaluations as dreaded tasks. If this occurs, it is because the supervisor has not learned how to perform evaluations in a constructive way. Few of us are so lucky that all our employees are self-motivated high performers who never need direction.

The basis for evaluation is a clear description of the tasks expected, the skill level for the task, and the level of individual judgment allowed. Such elements should form the basis of a signed agreement between workers and supervisors. An example of a performance contract between a director and an administrator is shown in Figure 2-6 below. Such a contract should spell out not only what the supervisor expects of staff, but also what the supervisor will do to facilitate the staff's work. The contract should be developed within the employee's first 30 days of employment. It should be discussed in detail at the start, and then reviewed at least semiannually so that the super-visor can offer suggestions.

THE TWO-WAY CONTRACT

Figure 2-6 Example of Performance contract.

From: Director of Health |

A performance contract requires the supervisor to define technical skills, knowledge, interpersonal behavior and the expectations for future development of staff. If well done, written annual evaluations justify promotion, or supplementary pay awards. Both the supervisor and employee will know before the formal meeting how the other has been performing. Behavior resulting in dismissal should be a rare event if periodic evaluations and constructive direction are performed fairly. If necessary, the periodic evaluations build a case for dismissal. When dismissal is necessary, it should be done in the probationary period, if possible. It is rare that people who are failing during probation turn out well later. Employee grievances referred to federal EEO programs are frequently the result of failing to discharge an ineffective employee during the probationary period. Good periodic evaluation will define any changes in interpersonal behavior that may be needed for effective work.

When poor work is seen in previously good performers, it is usually an indication of events occurring outside the work place, such as marital discord, alcoholism, or other drug dependence. Employee assistance (EA) counseling programs help these employees get back on track. These programs are most helpful when the supervisor presents them as coping mechanisms, rather than challenging the employee. The supervisor should simply specify which behavior deviates from the contract, and then recommend a particular counseling program. This approach avoids charges of favoritism or preferential treatment.

HORIZONTAL MANAGEMENT OR USE OF TEAMS

A management tool used with increasing frequency in government is team development. Team-based management is very different from management based on a hierarchical chain of command. It involves a group of people working together to achieve common goals using the skills of each member. Although the best examples of this approach are in heavy industry, it can work just as well in health departments. Most health department staff members are technically oriented, have special skills, and have good one- on-one interpersonal skills. With appropriate goals (delivery of prenatal care, installation of a septic tank, or treating an epidemic, for example), and the willingness to adapt procedures to meet these goals, a team is usually more successful than a single individual. Use of teams should enhance flexibility and sharing of responsibility among the members. Good administrators realize that they must be facilitators, letting staff members make most of the decisions. The supervisor may provide individual evaluations of performance but does not necessarily have to be a team leader on every project. Supervisors should help with scheduling, obtain resources for the team, and keep senior management advised of progress. Demonstrations of power do not get results.

PROGRAM EVALUATION

Administration of programs requires a different type of evaluation. At the federal or state level, this evaluation is very formal. Auditors trained in "systems review” are used, objectives are clarified, and audit trails are developed. Because most local health departments are tax-supported, with some money from third-party insurance programs (and in some cases fees for environmental services), citizens want to see their tax money used effectively and efficiently. They are usually more concerned about effectiveness:

Does it have the intended result? Without effectiveness, there is no point being concerned about efficiency. Past failures by the federal government to account for expenditure or monitor, performance has forced state and local agencies to prove they are not thieves!

The end of an audit trail is usually a clinical chart or an environmental inspection. Such a trail may start with a federal grant to a family planning program. The program then signs a contract for services with a local department and approves a document to transfer funds. Time and names of staff working in a family planning clinic are recorded and certified by supervisors. Money from the department's grant is used to reimburse the personnel office for staff time spent in the family planning clinic. Except for food service programs, there are few federal standards for either environmental or clinical outcomes. Most audits, unfortunately, emphasize process rather than outcome. There is an assumption that good records indicate good outcome. This is not true, but, because of failure to develop good outcome data, auditors are often left with nothing to review but a process,

AUDITS

As an example, take an audit of a family planning program. A local health director may know, based on experience, that with the resources available the department's efforts cannot change the birth rate. The best attainable outcome, with current resources, may be to keep the fertility rate from increasing. The federal auditors will be more concerned with whether the local agency has data on numbers of visits to clinics, and with the various tasks performed at each visit rather than with whether the fertility rate was stable or reduced.

Political concerns may influence an auditor's findings. For example, a burning interest the year of the audit may be whether all women have had an annual Pap smear. Not all women need an annual Pap test based on clinical evaluation and past medical history. If they don't all receive one, however, the auditor sampling charts and finding a lack of recorded Pap smears will stipulate payback of funds against the program. In an audit analysis, if there is no record, the task was not done. A blood pressure recording may be required at every visit, but in a busy clinic blood pressures may be taken but only recorded if there is an abnormality. With good supervision, this might be an acceptable practice. However, if 5% of charts fail to show a blood pressure record at each visit, a 5% reduction in funds will be charged as a penalty.

Before starting a program, you must know what the audit requirements will be so enough staff can be assigned to complete all these requirements. Staff morale and patient satisfaction might be better if more time were spent on counseling than on recording blood pressures, but unless this is agreed in advance, failure to record the blood pressure will be regarded as an indication of ineffective administration of the program.

With restaurant visits, failure to check off an item on an inspection sheet is a clear indication that the task was not performed. It may be, locally, that a decision was made to check off only items that failed to meet the standard. If there is a way of validating that unmarked items are unchecked items, such a recording procedure might be acceptable. The program's auditors need to know how you validate staff performance and programs out-come. Thus, you must have policies and standards written down so explicitly that auditors can demonstrate compliance with standards without excessive paperwork.

EFFECTIVENESS and EFFICIENCY

A program supervisor must not only review activities of individual staff members but also evaluate program outcomes for both effectiveness (did the program achieve its goals?) and efficiency (was the outcome achieved at lowest possible cost?). The supervisor has to account for all expenditure of resources when carrying out the program, whether these resources are time, supplies, equipment, or facilities. This will be discussed further in Chapter 4.

SALARY STRUCTURE

State departments of health must develop plans to hire and evaluate their employees. Locally, this is done by the city or county personnel system when the local department is not part of the state. The salary of a nurse working in the health department is compared with that of a nurse working in a school system, hospital, mental health facility, or rehabilitation program. Pay equity should be based on job equity. The skills, knowledge, and working conditions should be similar. Public health nurses are often required to make independent judgments based on greater knowledge and skill levels than nurses working on hospital wards. Consequently, nurses paid at a hospital general-duty staff-nurse pay scale may be remunerated at the wrong level. Health department administrators must watch for such inequities. Similar consideration must be given to all other health department employees.

A state health department may have over 5,000 full- and part-time employees. Local health departments may have less than 100 employees. Despite the difference in numbers, all are expected to provide equal treatment of their employees. The state agency must be sure that all the state rules for employment, including hiring standards, evaluation standards, and causes for dismissal, are enforced in an equitable manner. Although this might seem simple, the biggest problems that occur in management are caused by failure to supervise individuals fairly. In local health departments, this may be even more difficult. A local health director employs staff with similar skills that are paid from different sources such as a county, city, or state payrolls. All nurses in a single family-planning clinic may do a similar job. Yet, the different nurses paid from different payrolls will have different benefits, despite doing the same work. This may occur because lack of state funds forces a community to hire additional public health staff from local funds. The staff is supervised by the same local health director. In larger communities, the health director may administer grants from the federal government or private foundations. These grant-paid employees may not be employed in either the state or local community's civil service system. It is worth noting that several states, particularly in the Northeast, have a health department every separate city and County whether often only two and three employees in the local health department office with minimal supervision which is very did to that seen organized states such as Virginia or North Carolina.

Trying to manage staff where such inequities exist is difficult. There is no simple solution, except to take great care that all staff members see the system as operating as fairly as possible. The health director can do this only through supervisors who know they are held personally responsible for ensuring fair treatment of all employees.

PURCHASING

The purchasing function is often multi-jurisdictional in state and local agencies. In addition to buying or renting space in which to work, any health department needs fixed and disposable equipment and supplies to carry out its activities. This is done through a purchasing program. In state departments, where purchases can be made efficiently by buying for the entire state, the purchasing division is accountable to the chief fiscal officer. Train-car loads of medications paper, desks arid chairs, and computers may be ordered. Local departments may be given discretion to purchase certain supplies locally. A local director may have purchasing authority, not only from the state, but also from the local government. The local director needs an administrator or chief purchaser (depending on the size of the health district) who understands all the ins and outs of bidding for supplies on the open market. The purchasing manager must know which firms in the community must be included in the bidding process and how to prepare for sealed bids. He or she must understand all the audit and accounting variables in such purchasing.

It may be possible to use local group purchasing where a number of local jurisdictions or hospitals have developed group purchasing capability. Whether or not you can do this will depend on state and local law. This very technical area needs careful supervision. Failure to exert oversight of purchasing standards has cost more than one health director and administrator their jobs. Don't hesitate to call for help if this is a new area for you or if you have the slightest doubt about the capability of your staff in this area. Such help can be found in either local or state governments, often from the state comptroller or state auditor.

REQUIRED READING

Goldsmith S. & Eggers wd: Governing by Network. The Brookings Institute. 2004.

Essentials of Public Health: Chapters and 7, 6. Turnock B J; Jones & Bartlett. 2014

Essentials of Public Health Management, 3rd Edn. Chapters 8 and 9; Fallon FL, & Zgodzinski EJ, Jones & Bartlett, 2012

RECOMMENDED READING

The Future of Public Health in the 21st Century (Washington, DC: National Academy Press), 2003.

Who Will Keep the Public Healthy (Washington, DC: National Academy Press), 2003.

The Future of Public Health (Washington, DC: National Academy Press), 1988.

Townsend R: Up the Organization (New York: Knopf), 1978. This book is a classic and worth putting in your developing library.